|

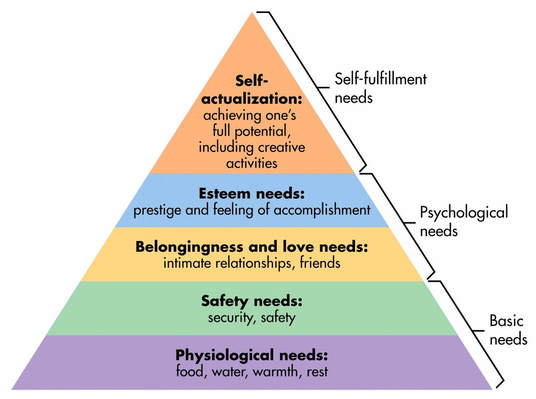

As an architect, I have spent close to thirty years carefully observing the world around me. These observations provoke ideas about ways that architecture can embody, express, and enhance the world and its myriad of cultures, rhythms, and beliefs. As a teacher of architecture, I have the opportunity to take these ideas accumulated over time and try them out as projects in the classroom. It's my responsibility as a teacher to be prepared with engaging projects that will educate, enlighten, and inspire my students as they explore the world of architecture. As a result, I have continuously added to my existing catalog of ideas and dutifully prepared each semester with a series of related projects for each class. This process of preparation can be very time-consuming and challenging. There's a lot of ground to cover from coming up with projects that work and flow together, to topical research, schedules, individual classroom lessons, etc., so I always try to prepare well ahead of each semester. Last Spring, as I was sifting through my large catalog of ideas, and my Fall curriculum was beginning to take shape, I just couldn't ignore the impact of this... One brief moment...a single post in my social media feed...and my teaching world had come undone. This is Malak. She was seven years old when she did this interview after fleeing violence in her Iraqi home to arrive at a refugee camp. The image of this young girl standing in the dust and chaos of a camp desperately trying to hold herself together would not leave my thoughts. To this day, this short video clip has a tremendous emotional impact on me. Malak and her desperate search for safety and hope was lodged in the front of my mind and not going anywhere. At that point, there was nothing else I could do except drop all of the plans I had made and develop a semester curriculum devoted to architecture for refugees. OK, so now what? What are my students supposed to get out of this? First, I knew they needed to hear Malak's story, as well as those of the other countless children and people in the midst of this crisis. I wanted my students to understand the significance and impact of events happening in the world, a macro view of life rather than the narrow but comfortable micro view that I see in the classroom every day. An organization like Preemptive Love Coalition, who is currently working in the area, gave us a wonderful window into this reality half a world away. Also important, because I'm teaching architecture here, was an understanding of architecture's ability to address issues that we see in a refugee crisis. I wanted my students to know what role architecture can play in all this chaos and destruction. Over the previous years, some of my classes have engaged in similar projects. We have looked at New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward and the devastating legacy of Hurricane Katrina...twice. We have also investigated the work done by Auburn University's Rural Studio and the potentiality for architecture to be helpful, inspiring, and affordable. All of those projects were useful while frantically setting up the next eighteen weeks of curriculum, but like I said earlier, they were only similar. Here was an international crisis happening halfway around the world affecting people from a distinctly different culture, living in a distinctly different geographical environment, being impacted by a completely different disaster scenario. To honor Malak and her fellow refugees, we needed a different kind of semester. Having taken feedback from students after each semester, I knew that one of their interests was working in teams. It was a frequent request that I had received. This project was the perfect opportunity to try it out on a large scale. Breaking students into teams works for us on a couple of levels; we can tackle bigger problems, like urban planning for refugee camps and cities, and it allows students to collaborate across classes. When designing for refugee camps and bombed out cities, it requires a different kind of architecture. To meet the unusual requirements for environments like these, students had to explore the design of temporary and economical structures that could be rapidly deployed and assembled. To house returning refugees, new approaches to building design, self-sufficiency, and living requirements had to be explored. Bringing these ideas home in the classroom, students read through "War and Architecture", a work by architect and theoretician Lebbeus Woods that addresses ideas for a new kind of architecture under these extreme and volatile conditions. Beyond all of these technical and physical requirements still lies the basic question of architecture meeting human need. Working to support children like Malak and their families meant that student designs also needed to be developed with a sensitivity to a culture beyond their own as well as to basic human need. In order to help students understand the concept of need in architecture, I took teacher training and turned it back in on the classroom using Mazlow's hierarchy of needs. A theory of psychologist Abraham Mazlow, this concept outlines a specific order of human need that determines a person's ability to survive, belong, and grow as an individual. Teachers study this to help them facilitate learning in the classroom by understanding and addressing pressures that affect students' ability to think and learn. As we discussed these principles with students, they were challenged to embrace this concept as they designed for their refugee clients. How can we allow a child like Malak to not only survive her circumstances, but also have the opportunity to thrive? This was a lot of work and thought to take on for eighteen weeks, but students are preparing this week to end their semester with a full public exhibition of their work. Each of them took on this challenge of a very different kind of learning experience and developed their own unique responses to the problems presented. Over our holiday break, I was fortunate enough to find another engaging video in my social media feed that I was able to once again share with my classes upon their return... Malak's story has another chapter...a happier one. Through this little girl's journey, I hope that our CCE architecture students have a broader, more informed, and more sensitive view of the world around them. From this experience, I honestly don't care if they remember common residential doorway widths or all of the commands in AutoCad. I just hope that, like me, they remember Malak and the potential for architecture to make a difference.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris Carson is a licensed architect, woodworker, and tsundoku enthusiast. He directs the Architecture Studios at Lewisville ISD's Career Center East. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed