|

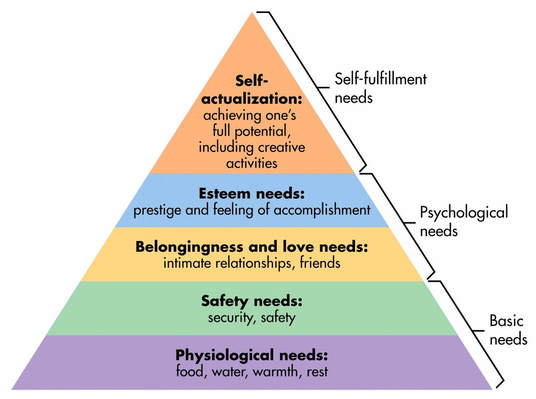

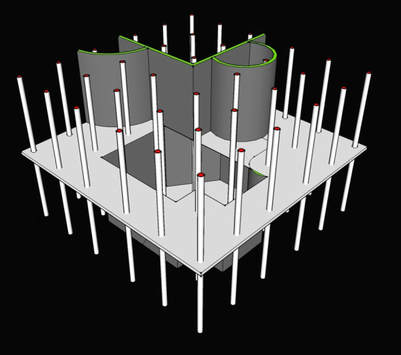

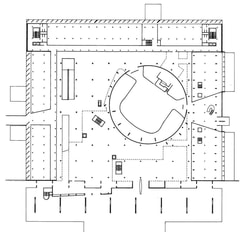

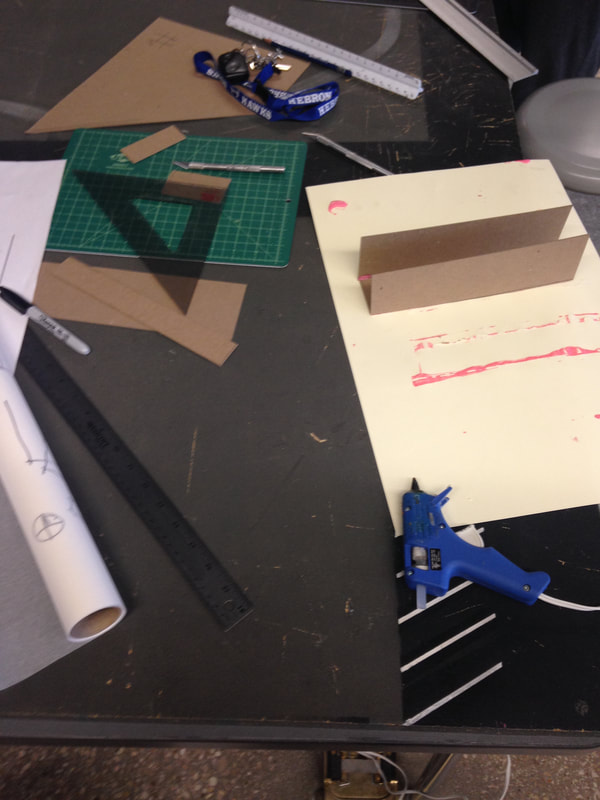

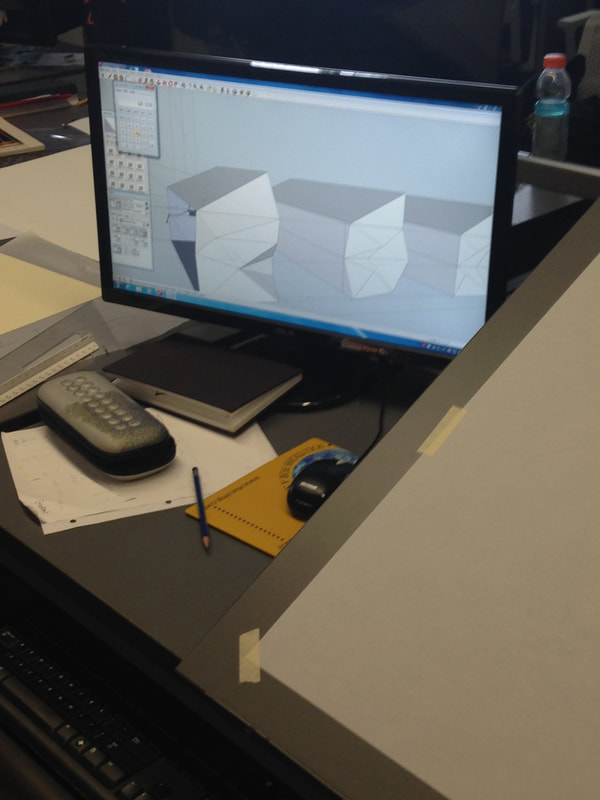

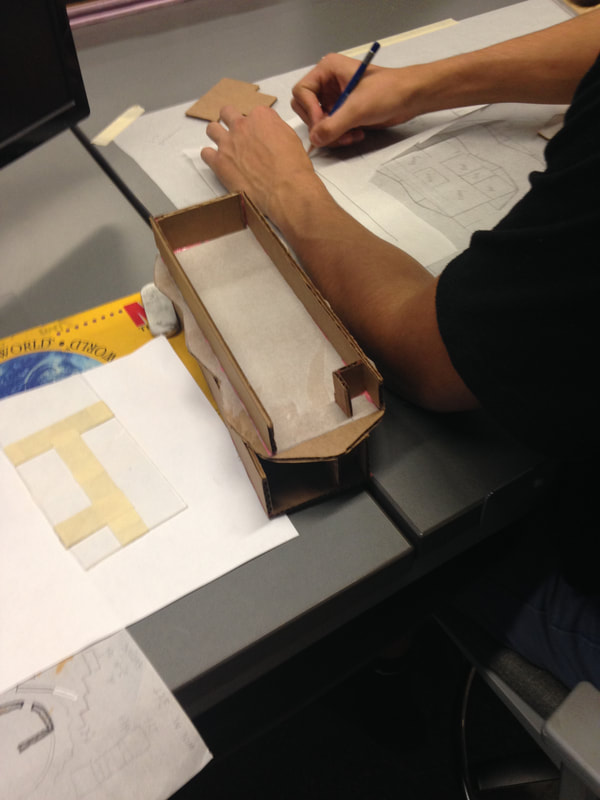

As an architect, I have spent close to thirty years carefully observing the world around me. These observations provoke ideas about ways that architecture can embody, express, and enhance the world and its myriad of cultures, rhythms, and beliefs. As a teacher of architecture, I have the opportunity to take these ideas accumulated over time and try them out as projects in the classroom. It's my responsibility as a teacher to be prepared with engaging projects that will educate, enlighten, and inspire my students as they explore the world of architecture. As a result, I have continuously added to my existing catalog of ideas and dutifully prepared each semester with a series of related projects for each class. This process of preparation can be very time-consuming and challenging. There's a lot of ground to cover from coming up with projects that work and flow together, to topical research, schedules, individual classroom lessons, etc., so I always try to prepare well ahead of each semester. Last Spring, as I was sifting through my large catalog of ideas, and my Fall curriculum was beginning to take shape, I just couldn't ignore the impact of this... One brief moment...a single post in my social media feed...and my teaching world had come undone. This is Malak. She was seven years old when she did this interview after fleeing violence in her Iraqi home to arrive at a refugee camp. The image of this young girl standing in the dust and chaos of a camp desperately trying to hold herself together would not leave my thoughts. To this day, this short video clip has a tremendous emotional impact on me. Malak and her desperate search for safety and hope was lodged in the front of my mind and not going anywhere. At that point, there was nothing else I could do except drop all of the plans I had made and develop a semester curriculum devoted to architecture for refugees. OK, so now what? What are my students supposed to get out of this? First, I knew they needed to hear Malak's story, as well as those of the other countless children and people in the midst of this crisis. I wanted my students to understand the significance and impact of events happening in the world, a macro view of life rather than the narrow but comfortable micro view that I see in the classroom every day. An organization like Preemptive Love Coalition, who is currently working in the area, gave us a wonderful window into this reality half a world away. Also important, because I'm teaching architecture here, was an understanding of architecture's ability to address issues that we see in a refugee crisis. I wanted my students to know what role architecture can play in all this chaos and destruction. Over the previous years, some of my classes have engaged in similar projects. We have looked at New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward and the devastating legacy of Hurricane Katrina...twice. We have also investigated the work done by Auburn University's Rural Studio and the potentiality for architecture to be helpful, inspiring, and affordable. All of those projects were useful while frantically setting up the next eighteen weeks of curriculum, but like I said earlier, they were only similar. Here was an international crisis happening halfway around the world affecting people from a distinctly different culture, living in a distinctly different geographical environment, being impacted by a completely different disaster scenario. To honor Malak and her fellow refugees, we needed a different kind of semester. Having taken feedback from students after each semester, I knew that one of their interests was working in teams. It was a frequent request that I had received. This project was the perfect opportunity to try it out on a large scale. Breaking students into teams works for us on a couple of levels; we can tackle bigger problems, like urban planning for refugee camps and cities, and it allows students to collaborate across classes. When designing for refugee camps and bombed out cities, it requires a different kind of architecture. To meet the unusual requirements for environments like these, students had to explore the design of temporary and economical structures that could be rapidly deployed and assembled. To house returning refugees, new approaches to building design, self-sufficiency, and living requirements had to be explored. Bringing these ideas home in the classroom, students read through "War and Architecture", a work by architect and theoretician Lebbeus Woods that addresses ideas for a new kind of architecture under these extreme and volatile conditions. Beyond all of these technical and physical requirements still lies the basic question of architecture meeting human need. Working to support children like Malak and their families meant that student designs also needed to be developed with a sensitivity to a culture beyond their own as well as to basic human need. In order to help students understand the concept of need in architecture, I took teacher training and turned it back in on the classroom using Mazlow's hierarchy of needs. A theory of psychologist Abraham Mazlow, this concept outlines a specific order of human need that determines a person's ability to survive, belong, and grow as an individual. Teachers study this to help them facilitate learning in the classroom by understanding and addressing pressures that affect students' ability to think and learn. As we discussed these principles with students, they were challenged to embrace this concept as they designed for their refugee clients. How can we allow a child like Malak to not only survive her circumstances, but also have the opportunity to thrive? This was a lot of work and thought to take on for eighteen weeks, but students are preparing this week to end their semester with a full public exhibition of their work. Each of them took on this challenge of a very different kind of learning experience and developed their own unique responses to the problems presented. Over our holiday break, I was fortunate enough to find another engaging video in my social media feed that I was able to once again share with my classes upon their return... Malak's story has another chapter...a happier one. Through this little girl's journey, I hope that our CCE architecture students have a broader, more informed, and more sensitive view of the world around them. From this experience, I honestly don't care if they remember common residential doorway widths or all of the commands in AutoCad. I just hope that, like me, they remember Malak and the potential for architecture to make a difference.

0 Comments

God is in the details. - Mies van der Rohe I have always found this quote about architecture interesting, and in many ways, I can identify with and relate to it. Far too often, architecture is focused and obsessed with the grand gesture or only the exterior form of a design. When having the chance to experience and observe really great architecture, I find it to be successful at all scales. From a distance, the building intrigues with a unique profile or powerful forms revealing themselves in a landscape. From a closer viewpoint, the building reveals dynamic spaces, a sense of materiality, craft, texture, and pattern that heighten the experience as well as change perception and awareness as one occupies and moves through it. Finally, as the building envelops us with its forms and surfaces, we are allowed the delight of discovering the small details. These are the moments where, if you are paying close attention, greatness happens. Here, we see the architect's focus on the smallest elements of a building, giving them the same care and diligence that we saw as we approached the building. In the details, we can see the same ideas and thoughts the architect laid out for us as we entered a room or turned a corner outside. The details give architects the opportunity for surprise -- the unexpected moment where we encounter something new or so well crafted we do a double-take and say, "Wow!". In the architecture studio, with the time we have allotted for students to work in a semester, it's always very difficult to get down to the level of the detail. A typical project in our studios lasts six to nine weeks. With all that has to be learned in order to conceptualize, rationalize, develop, and describe a design, we have to focus much of our energy on the big idea -- the building from a distance. So how do we help students understand the details of architecture? Field trips... Fortunately, Fort Worth and Dallas are home to a wide array of world-class architecture within easy reach during a school day. With fantastic organizations like the Dallas Architecture and Design Exchange and renown local architects like Mark Gunderson, students have the opportunity each semester to get expert guidance in understanding architecture created by the significant and influential architects they have studied in class. Here, students can see first-hand, architecture working at a variety of scales. Here, the details can be seen and appreciated in context.

In studio, we strive to build a foundation of design thinking and creative vision that provides students with skills to start their journey in architecture. In our regular pilgrimages to the significant architecture around us, students have an experience that helps them see how a truly great building brings it all together and offers a transcendent experience. Wait...he wants me to do what??! Research? I'm in architecture class. I thought we just drew in here. I just want to start designing my project. -Every CCE Architecture Student No student of mine has ever said this out loud, but I'm sure it has been thought many times. All throughout higher education and my professional career, I have understood and embraced the power and importance of research in architecture. Now I have to pass this critical concept on to high school students to prepare them for a future in this profession. In order to accomplish this, I typically set up projects with a variety of elements and situations that are intentionally unfamiliar to my students. This semester, my 2nd year class is designing shipping container houses for urban farms in central Detroit. The third year class is selecting the site for the project, master planning the neighborhood, and designing community structures to support the projects of the 2nd year class. Like I said...intentionally unfamiliar. I concluded my introduction of this project as follows: Me: "Alright, who in here is from or has lived in Detroit?" Students: .................................. Me: "Who in here is an experienced urban farmer? Students: .................................. Me: "OK. Anybody currently living in a house made from shipping containers?" Students: .................................. Me: "So as architects, how to we address a project like this? How do we start?" Students: "Umm...Research?" In previous semesters, I have seen students go through the motions of what I have asked them to do at the beginning of a project. They dutifully look up information, write facts down, put images on a poster, or post their findings to the class website. After about a week of work, they have amassed a fairly large collection of useful data that can be applied to their project and used to support a design solution. At this point, the pencil hits paper and all the research is jettisoned in a cloud of dust as they furiously scratch out the ideas that have been bouncing around in their heads over the previous week. It is difficult at this stage of an architectural education to teach students to look beyond the walls of a building and use information outside of architecture to drive a design -- but try I must. Architecture requires flexibility. Architects are trained in design, and we should have the ability to create any type of building anywhere in the world. Architectural training even takes some people into related fields such as industrial design, video game design, and movie animation. How are architects able to achieve this level of flexibility? Yes...research. Research is so important to architecture and design thinking that many architecture firms have established their own in-house research groups to address the variety of challenges within the profession: Office of Metropolitan Architecture and research group AMO Rafael Vinoly Kieran Timberlake Research is the way we figure out the best way to arrange the spaces for a specific building type. It's how we make the most appropriate material selections and the best way to assemble them. It's also the tool with which we shape our future. Research is how architecture becomes more user friendly, more sustainable, and more valuable to our lives. It's also how 10 high school students figure out the best designs for an urban farm community in the heart of Detroit. Click here to see our ongoing research that is being posted on the studio website. Feel free to check out the students' findings and leave a comment, word of encouragement, or even your own bit of research you would like to contribute.

I used to help my grandfather on the farm, driving tractors, raising crops and animals…at about 9 or 10 I started driving tractors. It showed me at an early age what hard work was all about and how dedicated you have to be, no matter what you do. -Tyson Chandler, Dallas Mavericks Center I grew up in the sticks...yes, it's true. My formative years were spent in rural Texas among hay fields and along the banks of the Colorado river. I learned how to drive on a Kubota tractor and was active in 4H. Mornings and evenings were spent tending to cattle and other farm animals. Family vacations were actually long weekends at county fairs around the state. Somehow the boy on the farm ended up in architecture school embracing the dynamic environment of the metropolis and developing a passion for Modernism. When I'm planning a semester for my classes, I try and work around a central concept on which all of the studio projects are based. This past Fall, we explored architecture in rural America. Having grown up in that environment, I have always had a keen interest in the subject. Once I understood architecture and had formed my own set of interests and opinions, I found myself inspired and constantly gravitating toward the unique forms, materials, and qualities of the rural landscape. The subject of rural architecture was incorporated in all classes during the semester and customized to the experience level and expectations for the students. First year students spent the second half of the semester analyzing traditional vernacular houses and using the information to develop their own updated version of a rural house for the 21st century: Second year students developed one project over the entire semester. Their task was to create a farmstead in three phases. The semester began with an exploration of shipping container architecture to create temporary living quarters and establish the farm: Phase two required the students to incorporate a rural-based business with their container house using pre-engineered metal building systems: Finally, the third phase completed the farmstead project with a permanent farmhouse based on traditional vernacular types. In each phase, students were required to incorporate their designs from the previous phase: Third year practicum students took a different route and explored the variety of ways that architecture can be used to support rural communities. After looking at the work of Auburn University's Rural Studio, students developed projects that addressed a common need that these communities would have: One of the interests I developed quickly during my undergraduate studies at Texas A&M was a love of books. There's something about architects and books. There's even a book about architects and their books. One of my favorite free time activities during those first years of school was to visit the central campus library and see what interesting architecture books I could find, check out, and peruse (while trying not to drool on the pages). One evening, amid the library stacks, I came across Le Corbusier's "Oeuvre Complete"...and it was over. I was instantly hooked. "Oeuvre Complete" is an 8 volume hardbound set of virtually every project and building completed by the French architect Le Corbusier. Corbusier is considered one of the masters of International Style Modernism that occurred at the turn of the 20th century. His work has become a staple of architecture schools worldwide. Students study his work repeatedly in history class and design studios. I went through every volume of that set, one by one, visually devouring every image and every word on every page. Many years later, after visiting some of his buildings and practicing as a professional, I can still say that I find Corbusier's work interesting and intriguing. Now I teach high school architecture...and I get to pass along my enthusiasm for Le Corbusier. Last year in our Advanced Architecture Studio, my students designed a house based on the use of a nine-square grid. This project was a natural fit for introducing Le Corbusier, so our research was based on an investigation of his career and work. Using this strategy gave my students a focused history lesson within the context of gathering tools and information to apply to their projects. As part of this research, students developed three-dimensional representations of Corbusier's "Five Points of a New Architecture"... ...parti diagrams of his buildings... ...as well as a timeline of his life and career. You can see the full web page of the students' research here. Once they had information on Corbusier, they were able to take what they had learned and apply it to their own projects. I think we had some really interesting results: As a teacher, I always hope that my students find the work I present them interesting and useful. This summer, we had two students attend UT Arlington's Architecture Seed Camp. I was able to be there the final day of camp to see the presentation of their work. As I was milling about the space in the Architecture building, I could see Corbusier's influence in the college work that the University had on display. When visiting with one of my students about her experience at camp, she told me "the instructors started talking about Le Corbusier, and I totally knew what they were talking about!"

Thank you Mr. Corbusier, for giving me something great to share. Well, we are almost nine weeks into the Fall semester and are hard at work wrapping up project number one. An objective that we had this year was to take the Architecture program further beyond the walls of our school and district. This objective was inspired by the writing of Alan November in his book Who Owns the Learning which was a subject of study over the summer break. You are already seeing the results in this blog post. You will also begin to see changes in the program's website. In addition to my own blog, each student in the program will have their own blog on our site that will allow them to write their thoughts and ideas on the projects and subjects we cover in class. As we progress through different projects this year, students will begin using other online and social networking tools to extend the reach of their work into the digital landscape of the Internet. Please feel free to take a look at all of the information and ideas posted by the students and provide comments on what you see. Part of what makes architecture successful is the input and critique provided by others, and we want to get feedback from outside of our own walls. One of the foundations of this program is the presentation of projects and work to architecture and design professionals. We think that our work can only get better by presenting our ideas to the world, so thanks in advance for taking the time to visit us. I hope you find the student work intriguing and exciting. I am amazed at the end of every project with what my students are capable of creating.

|

AuthorChris Carson is a licensed architect, woodworker, and tsundoku enthusiast. He directs the Architecture Studios at Lewisville ISD's Career Center East. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed